http://www.physio-pedia.com/Whiplash_Associated_Disorders

Whiplash Associated Disorders

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

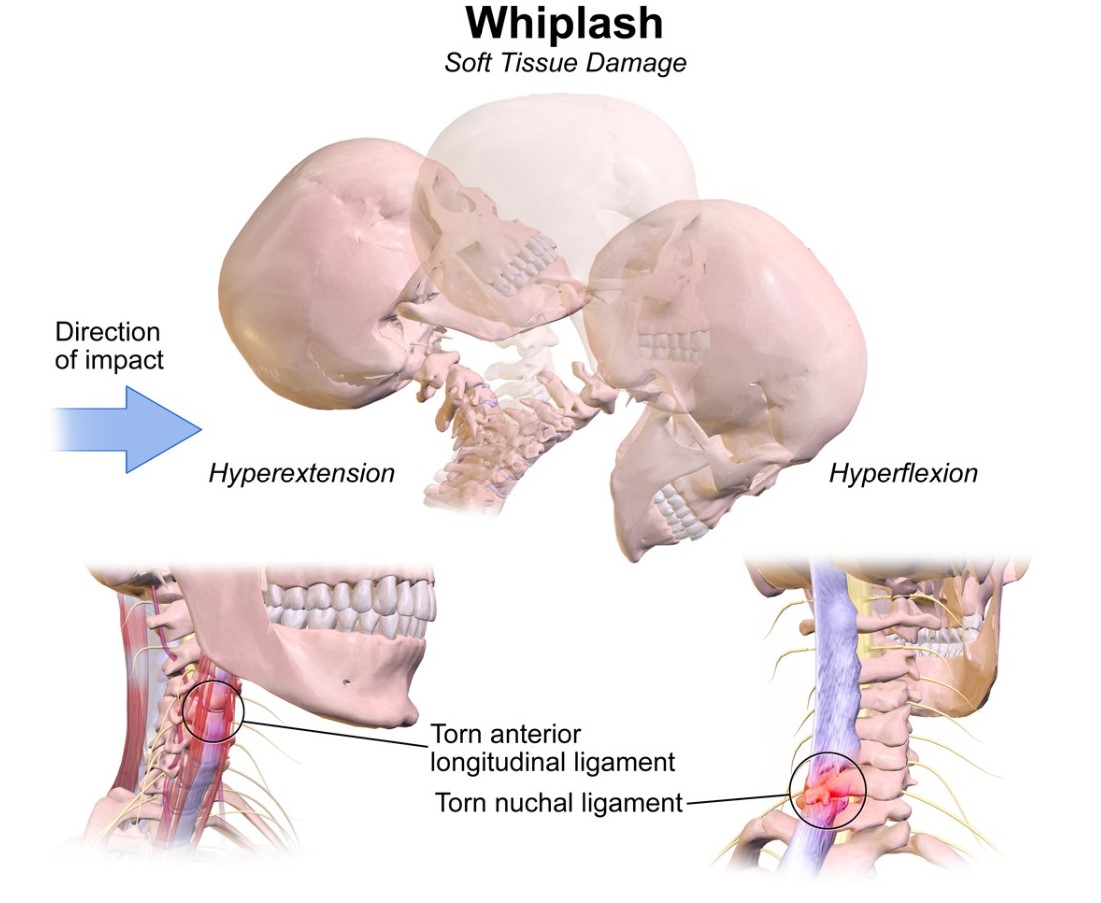

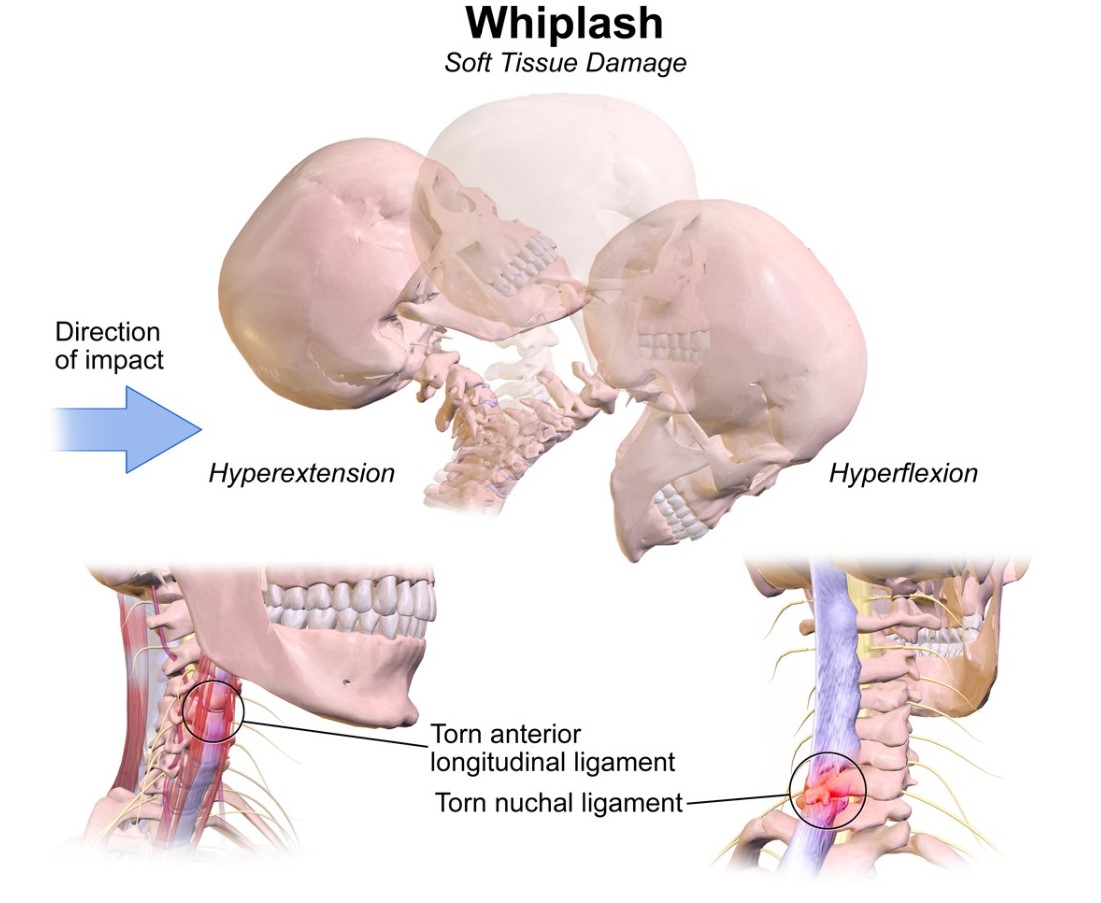

Whiplash and whiplash associated disorders (WAD) affects variable areas of the cervical spine, depending on the force and direction of impact as well as many other factors. In a whiplash injury, bony structures, ligamentous structures, muscles, neurological structures, and other connective tissue may be affected. Anatomic causes of pain can be any of these structures, with the strain injury resulting in secondary edema, hemorrhage, and inflammation.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process

The mechanism of injury is variable, usually involving a motor vehicle accident but also including causes such as sports injury, child abuse, blows to the head from a falling object, or similar accelleration-decceleration event.

Síndrome del latigazo cervical

Anatomía relevante

Whiplash y trastornos del latigazo cervical (WAD) afecta a las zonas variables de la columna cervical, dependiendo de la fuerza y dirección del impacto, así como muchos otros factores. En un latigazo cervical, estructuras óseas, estructuras ligamentosas, los músculos, las estructuras neurológicas y otros tejidos conectivos pueden verse afectados. Causas anatómicas del dolor pueden ser cualquiera de estas estructuras, con la lesión cepa resultante en el edema secundaria, hemorragia, y la inflamación.

Mecanismo de la lesión / proceso patológico

El mecanismo de lesión es variable, por lo general implica un accidente de vehículo de motor, sino también incluyendo causas como la lesión de los deportes, el abuso infantil, golpes en la cabeza de un objeto que cae, o evento de aceleración-desaceleración similar.

Clinical Presentation

Whiplash associated disorders are most frequently due to a car accident. The most common symptoms are sub-occipital headache and / or neck pain that is constant or motion-induced. There may be up to 48 hrs delay of symptom onset from the initial injury. Other associated symptoms include mechanical cervical spine instability and neurological symptoms, dizziness, tinnitus, visual disturbances, difficulty sleeping due to pain, and difficulty concentrating / bad memory. It is important to have a thorough spinal examination and neurological examination in patients with WAD to screen for delayed onset of the cervical spine instability or myelopathy [1]. A whiplash can be an acute or chronic disorder. In acute whiplash symptoms last no more than 2-3 months, while in chronic whiplash symptoms last longer than three months. Various studies indicate that there can be a spontaneous recovery within 2-3 months[2]. According to the QTF-WAD 85% of the patients recover within 6 months[3].

QTFC (Quebec Task Force Classification)

The Quebec Task Force was a task force sponsored by a public insurer in Canada. They submitted recommendations regarding classification and treatment of WAD, which was used to develop a guide for managing whiplash in 1995. An updated report was published in 2001. Each of the grades corresponds to a specific treatment recommendation.

| QTFC Grade | Clinical presentation |

| 0 |

No complaint about neck pain

No physical signs

|

| I |

Nec complaints of pain, stiffness or tenderness only

No physical signs

|

| II |

Neck complaint

Musculoskeletal signs including

|

| III |

Neck complaint

Musculosceletal signs

Neurological signs including:

|

| IV | Neck complaint and fracture or dislocation |

MQTFC (Modified Quebec Task Force Classification) [4]

Proposed

classification grade

| Physical and psychological impairments present |

| WAD 0 |

No complaints about neck pain

No physical signs

|

| WAD I |

No complaints of pain, stiffness or tenderness only

No physical signs

|

| WAD IIA |

Neck complaint

Motor impairment

Sensory Impairment

|

| WAD IIB |

Neck complaint

Motor impairment

Sensory Impairment

Psychological impairment

|

| WAD IIC | Neck complaint

Motor impairment

Sensory Impairment

Psychological impairment

|

| WAD III |

Neck complaint

Motor impairment

Sensory Impairment

Neurological signs of conduction loss including:

Psychological impairment

|

| WAD IV | Fracture or dislocation |

Diagnostic Procedures

Canadian C-Spine Rule (CCR): algorithm to determine the necessity for cervical spine radiography in alert and stable patients presenting with trauma and cervical spine injury. [5]

Management / Interventions

Management approaches for patients with WAD are poorly researched. These patients often do not fit into treatment categories as defined for other cervical pain problems due to multiple factors, and even within the WAD group there are multiple variances which warrant individualized treatment approaches. The most recent evidence supports the use of Sterling's classification system for WAD. [6]

ACUTE WHPLASH

Whiplash – associated disorder (WAD) is a debilitating and costly condition of at least 6-month duration. Although the majority of patients with whiplash show no physical signs [7] studies have shown that as many as 50% of victims of whiplash injury (grade 1 or 2 WAD) will still be experiencing chronic neck pain and disability six months later [8]. In most cases, symptoms are short lived, but a substantial minority go on to develop LWS (late whiplash syndrome), i.e. persistence of significant symptoms beyond 6 months after injury [9].

Treatment in acute whiplash can be delayed and confused by multiple social, economic, and psychological factors [10]. Psychological factors such as depression, anxiety, expectations for recovery, and high psychological distress have been identified as important prognostic factors for WAD patients. Coping strategies such as diverting attention and increasing activity are related with positive outcomes [7]. In order to avoid chronicity, it is important to screen for prognostic factors in time. According to Walton et al, there are 9 significant predictors [7]:

Treatment in acute whiplash can be delayed and confused by multiple social, economic, and psychological factors [10]. Psychological factors such as depression, anxiety, expectations for recovery, and high psychological distress have been identified as important prognostic factors for WAD patients. Coping strategies such as diverting attention and increasing activity are related with positive outcomes [7]. In order to avoid chronicity, it is important to screen for prognostic factors in time. According to Walton et al, there are 9 significant predictors [7]:

- No postsecondary education

- Female gender

- History of previous neck pain

- Baseline neck pain intensity above 55/100

- Presence of neck pain at baseline

- Presence of headache at baseline

- Catastrophizing: there is evidence of catastrophizing and reinterpreting pain sensations being maladaptive for patients exposed to whiplash trauma [11].

- WAD grade 2 or 3

- No seat belt in use at time of collision [7]

Education provided by physiotherapist or general practitioner is important in prevention of chronic whiplash. The most important goals of the interventions are:

- Reassuring the patient

- Modulating maladaptive cognitions about WAD

- Activating the patient [7]

There is strong evidence for most forms of verbal education for whiplash patients in order to reduce pain, enhance neck mobility, and improve outcome. In acute patients oral information is equally efficacious as an active exercise program. In acute whiplash patients, a short oral education session is effective in reducing pain and enhancing mobility and recovery. Different types of education [7]:

1. Oral Education: there is strong evidence for providing oral education concerning the whiplash mechanisms and emphasizing physical activity and correct posture. It has better effect on pain, cervical mobility, and recovery, compared to rest and neck collars. Furthermore oral education would be as effective as active physiotherapy and mobilization.

2. Psycho – educational video: A brief psycho-educational video at bedside seems to have a profound effect on subsequent pain and medical utilization in acute whiplash patients, compared to the usual care [7].

3. Advice according to The Whiplash Book [9]:

- Reassurance that prognosis following a whiplash injury is good.

- Encouragement to return to normal activities as soon as possible using exercises to facilitate recovery

- Reassurance that pain is normal following a whiplash injury and patients should use analgesia consistently to control this

- Advice against using a soft collar [9].

Conclusions of the Cochrane review (Gross A., et al., Patient education for neck pain 2012):

With the exception of one trial, this review has not shown effectiveness for educational interventions, including advice to activate, advice on stress-coping skills, workplace ergonomics and self-care strategies. Future research should be founded on sound adult learning theory and learning skill acquisition [12].

With the exception of one trial, this review has not shown effectiveness for educational interventions, including advice to activate, advice on stress-coping skills, workplace ergonomics and self-care strategies. Future research should be founded on sound adult learning theory and learning skill acquisition [12].

Chronic Whiplash

Patients with type I and Type II WAD-whiplash showed good results in a multimodal treatment program including exercises and group therapy. At 6 month follow-up, 65% of subjects reported complete return to work, 92% reported partial or complete return to work, and 81% reported no medical or paramedical treatments over 6 months[13]. Some studies show that the physical therapy program should include coordination exercises[14]

In patients with chronic WAD, negative thoughts are very important factors. Self-efficacy, a measure of how well an individual believes he can perform a task or specific behavior and emotional reaction in stressful situations, was the most important predictor of persistent disability in those patients [15]

The negative thoughts and pain behavior can be influenced by specialists and physical therapists by educating patients with chronic WAD about the neurophysiology of pain. Improvement in pain behavior resulted in improved neck disability and increased pain-free movement performance and pain thresholds according to a pilot study [16]

The negative thoughts and pain behavior can be influenced by specialists and physical therapists by educating patients with chronic WAD about the neurophysiology of pain. Improvement in pain behavior resulted in improved neck disability and increased pain-free movement performance and pain thresholds according to a pilot study [16]

Interventions with a combination of cognitive, behavioural therapy with physiotherapy including neck exercises is effective in the management of WAD patients with chronic neck pain[17][18], as also recommended by the Dutch clinical guidelines for WAD [19].

Another treatment is the use of cervical radiofrequency neurotomy (CRFN). It is a neuroablative procedure used to interrupt nociceptive pathways, and has been supported by several studies in patients with chronic WAD. A prospective study with chronic WAD patients who underwent CRFN treatment, showed an improvement in 70% of patients based on a number of parameters including Neck Disability Index and cervical range of motion [20].

Another treatment is the use of cervical radiofrequency neurotomy (CRFN). It is a neuroablative procedure used to interrupt nociceptive pathways, and has been supported by several studies in patients with chronic WAD. A prospective study with chronic WAD patients who underwent CRFN treatment, showed an improvement in 70% of patients based on a number of parameters including Neck Disability Index and cervical range of motion [20].

There are also invasive interventions for the treatment of chronic WAD. Radiofrequency neurotomy appears to be supported by the strongest evidence, although relief is not permanent. Other interventions are sterile water injections, saline injections, botulinum toxin injections, cervical discetomy and fusion, even though it’s not clear whether this treatments are actually beneficial. Further research is required to determine the efficacy and the role of invasive interventions in the treatment of chronic WAD[21].

In order to objectify and evaluate patients with whiplash disorders, following instruments can be used: Visual Analoge Scale (VAS), Neck Disability Index, day schedule [22].The neck disability index has been tested reliable and valid as a measure of neck disability[23].

In order to objectify and evaluate patients with whiplash disorders, following instruments can be used: Visual Analoge Scale (VAS), Neck Disability Index, day schedule [22].The neck disability index has been tested reliable and valid as a measure of neck disability[23].

EVIDENCE CONCERNING IMMOBILIZATION

| AUTHOR | CONCLUSION | LEVEL |

| Quebec Task Force 1988 [24] | Prolonged immobilization may increase scar tissue in the neck and reduce cervical mobility | 2B |

| Mealey et al 1986 [25] | Initial immobilization after whiplash injuries gave rise to prolonged symptoms. A more rapid improvement can be achieved by early active management without any consequent increase in discomfort | 3A |

| Borchgrevink GE et al 2008 [26] | Advice to “act as usual” plus NSAIDs significantly improved some symptoms (including pain during daily activities, neck stiffness, memory, concentration, and headache) after 6 months compared with immobilisation plus 14 days' sick leave plus NSAIDs | 1A |

| Teasell R.W. et al 2010 [27] | Immobilization with a soft collar is less effective than active mobilization and no more effective than advice to act as usual. Active mobilization is associated with reduced pain intensity and limited evidence that mobilization may also improve ROM, although it is not clear whether active mobilization is any more effective than advice to act as usual. | 1A |

EVIDENCE CONCERNING THE USE OF (SOFT) COLLAR

| AUTHOR | CONCLUSION | LEVEL |

| Schnabel et al 2004 [28] | Early exercise therapy is superior to the collar therapy in reducing pain intensity and disability for whiplash injury | 2B |

| Binder A. 2008 [26] | Instruction on mobilization exercises may be more effective than a soft collar at reducing pain at 6 weeks in people treated within 48 hours of a whiplash injury who all also took NSAIDs | 1A |

| Schnabel M et al 2008 [26] | Exercises significantly reduce the proportion of people with neck pain at 6 weeks compared with a soft collar and significantly reduce pain and disability at 6 weeks | 1A |

EVIDENCE CONCERNING THE ADVICE TO “ACT AS NORMAL”

| AUTHOR | CONCLUSION | LEVEL |

| Binder A 2008 [26] | Advice to "act as usual" plus NSAIDs may be more effective at 6 months than immobilization plus 14 days sick leave plus NSAIDs at improving neck stiffness in people with acute whiplash | 1A |

| Borchgrevink GE et al 2008 [26] | Advice to “act as usual” plus NSAIDs significantly improved some symptoms (including pain during daily activities, neck stiffness, memory, concentration, and headache) after 6 months compared with immobilisation plus 14 days' sick leave plus NSAIDs | 1A |

| Yadla S et al 2008 [29] | Early mobilization and return to activity may offer the best chance for recovery. | 1A |

| Teasell R.W. et al 2010 [27] | It does not appear that providing educational information during the acute phase provides a significant measurable benefit. There is some indication that oral and/or video presentation of educational information may be more effective than the distribution of pamphlets. | 1A |

EVIDENCE CONCERNING PHYSICAL THERAPY

| AUTHOR | DISCUSSION | LEVEL |

| Verhagen AP 2008 [26] | Limited evidence that active and passive interventions seemed more effective than no treatment. Less convincing evidence about active interventions compared with passive ones | 1A |

| Binder A 2008 [26] | Instruction on mobilization exercises may be more effective than a soft collar at reducing pain at 6 weeks in people treated within 48 hours of a whiplash injury who all also took NSAIDs | 1A |

| Lamb S et al 2013 [30] | Physiotherapy is recommended by several clinical guidelines. Recommended treatments include manual therapy, exercise, advice, and recognition of anxiety and psychological problems | 2A |

| Schnabel M et al 2008 [26] | Exercises significantly reduced the proportion of people with neck pain at 6 weeks compared with a soft collar and significantly reduced pain and disability at 6 weeks | 1A |

| Scholten – Peeters G et al 2008 [26] | No significant difference between physiotherapy (exercise or mobilization) and usual care in pain intensity, headache, or work activities measured at 8, 12, 26, or 52 weeks | 1A |

| Söderlund A 2008 [26] | No significant difference between a regular exercise regimen versus the same exercise regimen plus instructions in disability or pain after 3 or 6 months | 1A |

| Binder A 2008 [26] | Multimodal treatment (postural training, psychological support, eye fixation exer- cises, and manual treatment) may be more effective at improving pain at 1 and 6 months in people with whiplash due to a road traffic accident in the previous 2 months | 1A |

| Teasell R.W. et al 2010 [27] | Exercise programs are significantly more effective in reducing pain intensity over both the short and medium term. Conversely, supplemental exercise programs added to mobilization programs may not be any more beneficial than mobilization programs alone | 1A |

| Drescher K et al 2008 [31] | Moderate evidence to support the use of postural exercises for decreasing pain and time off work in the treatment of patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders. No evidence exists to support the use of postural exercises for increasing neck range of motion. Conflicting evidence in support of neck stabilization exercises in the treatment of patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders. | 1A |

Example physical therapy:http://www.physio-pedia.com/Manual_Therapy_and_Exercise_for_Neck_Pain:_Clinical_Treatment_Tool-kit

Differential Diagnosis

Cervical radiculopathy

Facticious disorder

Polymyalgia Rheumatica

Traumatic Brain Injury

Cervical herniated disk

Cervical myelopathy

Cervical osteoarthritis

Infection or osteomyelitis

Inflammatory rheumatologic disease

Malingering

Psychogenic pain disorder

Referred pain from cardiothoracic structures

Tumor or malignancy of cervical spine

Facticious disorder

Polymyalgia Rheumatica

Traumatic Brain Injury

Cervical herniated disk

Cervical myelopathy

Cervical osteoarthritis

Infection or osteomyelitis

Inflammatory rheumatologic disease

Malingering

Psychogenic pain disorder

Referred pain from cardiothoracic structures

Tumor or malignancy of cervical spine

Vascular abnormality of cervical structures

Key Evidence

Resources

Presentations

| Management of Cervical Spine Fractures

This presentation, created by Omar Valdezm, Kimberly Whitcher, Heather Williams, and Carcy Wright; Texas State DPT Class.

|

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)

References

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Delfini R, Dorizzi A, Facchinetti G, Faccioli F, Galzio R, Vangelista T. Delayed post-traumatic cervical instability. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:588-95. (1)

- ↑ Gargan MF, Bannister GC. The rate of recovery following whiplash injury. Eur Spine J 1994;3:162 (2)

- ↑ Bekkering GE. Et al. KNGF-richtlijn: whiplash. Nederlands tijdschrift voor fysiotherapie nummer3/jaargang 11. (1)

- ↑ Sterling M., Man Ther. 2004 May;9(2):60-70. A proposed new classification system for whiplash associated disorders--implications for assessment and management.

- ↑ Stiell IG, Clement CM, McKnight RD, Brison R, Schull MJ, Rowe BH, Worthington JR, Eisenhauer MA, Cass D, Greenberg G, MacPhail I, Dreyer J, Lee JS, Bandiera G, Reardon M, Holoroyd B, Lesiuk H, Wells GA. The Canadian c-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(26): 2510-2518.

- ↑ Sterling M, Jull G, Kenardy J. Physical and psychological factors maintain long-term predictive capacity post-whiplash injury. Pain. 2006;122:102-108.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Meeus M, Nijs J, Hamers V, Ickmans K, Oosterwijck JV. Pain Physician. The efficacy of patient education in whiplash associated disorders: a systematic review. 2012 Sep-Oct;15(5):351-61. LEVEL 1A

- ↑ Ferrari R, Rowe BH, Majumdar SR, Cassidy JD, Blitz S, Wright SC, Russell AS. Simple Educational Intervention to Improve the Recovery from Acute Whiplash: Results of a Randomized, Controlled Trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Aug;12(8):699-706. LEVEL 2A

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Lamb SE, Gates S, Underwood MR, Cooke MW, Ashby D, Szczepura A, Williams MA, Williamson EM, Withers EJ, Mt Isa S, Gumber A; MINT Study Team. Managing Injuries of the Neck Trial (MINT): design of a randomised controlled trial of treatments for whiplash associated disorders. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007 Jan 26;8:7. LEVEL 2C

- ↑ Yadla S, Ratliff JK, Harrop JS. Whiplash: diagnosis, treatment, and associated injuries. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008 Mar;1(1):65-8. LEVEL 1A

- ↑ Carstensen TB. The influence of psychosocial factors on recovery following acute whiplash trauma. Dan Med J. 2012 Dec;59(12):B4560. LEVEL 2A

- ↑ Gross A., et al., Patient education for neck pain. COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS. 2012;3

- ↑ Vendrig AA, Akkerveeken PF, McWhorter KR (2000). Results of a multimodal treatment program for patients with chronic symptoms after a whiplash injury of the neck. Spine, 25 (2): p.238–244 (4)

- ↑ Aris Seferiadis, Mark Rosenfeld (2004). A review of treatment interventions in whiplash-associated disorders, Eur Spine J. (13) nr.5: p387-397 (1)

- ↑ Bunketorp L, Lindh M, Carlsson J, Stene-Victorin E (2006). The perception of pain and pain related cognition in subacute whiplash-associated disorders: its influence on prolonged disability. Disabil Rehabil, 28(5): p.271–279 (2)

- ↑ Jessica Van Oosterwijck, Jo Nijs, PhD;1-3* Mira Meeus, Steven Truijen, Julie Craps, Nick Van den Keybus, Lorna Paul (2011). Pain neurophysiology education improves cognitions, pain thresholds, and movement performance in people with chronic whiplash: A pilot study, Journal of rehabilitation research and development, (48) nr.1: p43-58 (3)

- ↑ Hansen IR, et al. Neck exercises, physical and cognitive behavioural-graded activity as a treatment for adult whiplash patients with chronic neck pain: design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC musculoskelet disord. 2011; 12

- ↑ Seferiadis A, Rosenfeld M, Gunnarsson R: A review of treatment interventions in whiplash-associated disorders70. EurSpine J 2004, 13(5):387-397. (1)

- ↑ van der Wees PJ, Jamtvedt G, Rebbeck T, de Bie RA, Dekker J, Hendriks EJ: Multifaceted strategies may increase implementation of physiotherapy clinical guidelines: a systematic review. AustJPhysiother 2008,54(4):233-241.(1

- ↑ Prushansky T, Pevzner E, Gordon C, Dvir Z (2006). Cervical radiofrequency neurotomy in patients with chronic whiplash: a study of multiple outcome measures. J Neurosurg, 4(5): p.365–373.

- ↑ Robert W Teasell, et al. A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): Part 5 – surgical and injection-based interventions for chronic WAD. Pain res manag.2010. 15(5); 323-334. (1)

- ↑ Bekkering GE. Et al. KNGF-richtlijn: whiplash. Nederlands tijdschrift voor fysiotherapie nummer3/jaargang 11. (1)

- ↑ Vernon H. The neck disability index: patients assessment and outcome monitoring in whiplash. Journal of Muskuloskeletal Pain 1996 vol. 4(4): 95-104.(2)

- ↑ Söderlund A, Olerud C, Lindberg P. Acute whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): the effects of early mobilization and prognostic factors in long-term symptomatology. Clin Rehabil. 2000 Oct;14(5):457-67. LEVEL 2B

- ↑ Mealy K, Brennan H, Fenelon GC. Early mobilization of acute whiplash injuries. Br Med J Clin Res Ed). 1986 Mar 8;292(6521):656-7. LEVEL 3A

- ↑ 26.00 26.01 26.02 26.03 26.04 26.05 26.06 26.07 26.08 26.09 26.10 Binder AI. Neck pain. Clin Evid (Online). 2008 Aug 4;2008. LEVEL 1A

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Teasell RW, McClure JA, Walton D, Pretty J, Salter K, Meyer M, Sequeira K, Death B. A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): part 2 - interventions for acute WAD. Pain Res Manag. 2010 Sep-Oct;15(5):295-304. LEVEL 1A

- ↑ Schnabel M, Ferrari R, Vassiliou T, Kaluza G. Randomised, controlled outcome study of active mobilisation compared with collar therapy for whiplash injury. Emerg Med J. 2004 May;21(3):306-10. LEVEL 2B

- ↑ Yadla S, Ratliff JK, Harrop JS. Whiplash: diagnosis, treatment, and associated injuries. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008 Mar;1(1):65-8. LEVEL 1A

- ↑ Lamb SE, Gates S, Williams MA, Williamson EM, Mt-Isa S, Withers EJ, Castelnuovo E, Smith J, Ashby D, Cooke MW, Petrou S, Underwood MR; Managing Injuries of the Neck Trial (MINT) Study Team. Emergency department treatments and physiotherapy for acute whiplash: a pragmatic, two-step, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 Feb 16;381(9866):546-56. LEVEL 2A

- ↑ Drescher K, Hardy S, Maclean J, Schindler M, Scott K, Harris SR. Efficacy of postural and neck-stabilization exercises for persons with acute whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review. Physiother Can. 2008 Summer;60(3):215-23 LEVEL 1A

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario